I've launched an effort to avoid studying for a stats quiz tomorrow, and it's reaching heroic proportions. I've been thinking about language.

One of my favorite philosophers, Merleau-Ponty, thinks of language as another sense organ. It is something that makes the world around us more concrete; it helps us get a grip on things, helps us apprehend the world(in both senses of the word, perhaps). He has an interesting story about the development of language where, among other things, the babbling phase in children corresponds to pre-vocalized thoughts and dreams in adults. There is a reaching for (but not quite a grasping of) a thing or situation that remains fuzzy precisely because it isn't fleshed out with language. Accordingly, he also says that the word is the flesh of the thought. The use of the word "flesh" in this context means that Merleau-Ponty is trying to say that the word makes thought both something sensible and something we sense with.

We've all had the experience of having a brilliant thought that we try to express in words. I know I've had my share of brilliant thoughts, oh yes. As soon as I open my mouth, however, my brilliant thought seems downright silly. This is a general rule for me. I've also had the experience of describing my dreams to others--I feel like I'm half-reporting and half-creating-on-the-spot. And when I'm done describing the dream it always feels like I've left something out and put something in that wasn't there before. These are the experiences that hint at the sense of language that Merleau-Ponty is giving us.

I'm fascinated by this account of language. I still have to suspend my endorsement of it since I haven't had the time to consider all of its implications. But as a practicing member of the LDS faith I get the feeling that it is right. In the church we often talk about "bearing" our testimonies. This refers to the practice of avowing a conviction that certain doctrines of the gospel (and certain historical facts about the church) are true. One church leader, Elder Boyd K. Packer, is well-known for encouraging members to get up and bear their testimonies even when they aren't so sure what they believe. He says (paraphrasing) that "a testimony is to be found in the bearing of it."

For a long time I've thought that this statement is best understood from two different perspectives: (1) as a statement about cognitive conditioning, from the perspective of a non-believer, and (2) as a statement about the kind of spiritual knowledge that results from taking a leap of faith, from the perspective of a believer. For the non-believer, this must be a frightening statement. Somehow, if you want to believe in something and you say you believe in it, it suddenly becomes true to you. I've tried this on multiple occasions and my experience has always confirmed Elder Packer's promise. But now we're led to ask ourselves if we're only deceiving ourselves.

Not from Merleau-Ponty's point of view. By putting some sentiment (or maybe even a pre-sentiment) into words, we are giving it flesh. But this creation, the word, now acts as something with which we can try and grasp at the world. If these words fall flat and fail to hook up meaningfully with the rest of our world, they become a negation of themselves and we realize we have said something wrong. But if, by hearing these words we speak, the world becomes sharper and more focused, then these words become evidence for us that we have spoken truth. This, of course, is more of a phenomenological assessment, rather than a logical one. Logically speaking, all of us have had our worlds "focused" by a logical fallacy, or even by something that was, in some respect, untrue. But this is no problem if you consider that even a logical fallacy or a "partial truth" can bring us closer to truth. After all, the whole history of science is a story of partial truths bringing us closer to what we hope is a particular realm of truth.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

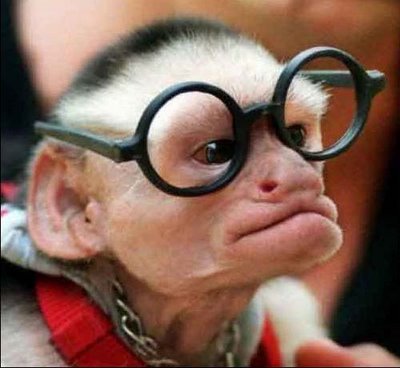

Batdog is perplexed.

About Me

The Family Circle

Photography Links

A non-comprehensive index of friendly blogs

- the Garv

- steph lewis

- Stacy and Matt

- Welsh Mustard

- I (heart) Austin

- the crandizzles

- The Krebs Cycle

- Bussell and Retsy

- Brooke is in mesa

- owen(s) the saints

- Matt and Jess Wood

- A Brown accountant

- by virtue of a faculty

- lisa and tyler packard

- The Chases, Las Vegas

- eric (and carly) the red

- Boyces without borders

- Life just got sweet for Hill

- the Josh and Jackie Show

- from the desk of Lord John

- Bunnies are not dogs, Laura

- the Westovers way over west

- King Arthur and Queen Sharee

- the gradual frenchification of Mer

- Kylee: matchmaker made in heaven

Spontaneously Changing Picture Box

Batdog is perplexed.

No comments:

Post a Comment